Prelude LP—Cello Suite No. 1: Prelude

I chose the extremely famous “Prelude” from Johann Sebastian Bach’s Cello Suite No. 1 to be the first single and title track from my upcoming debut album, Prelude LP, as an exercise in audacity (the audacity to release a classical recording with mistakes) and a heartfelt welcome to my fans to finally embark with me on this journey I’ve been postponing for far too long. TL;DR: welcome!

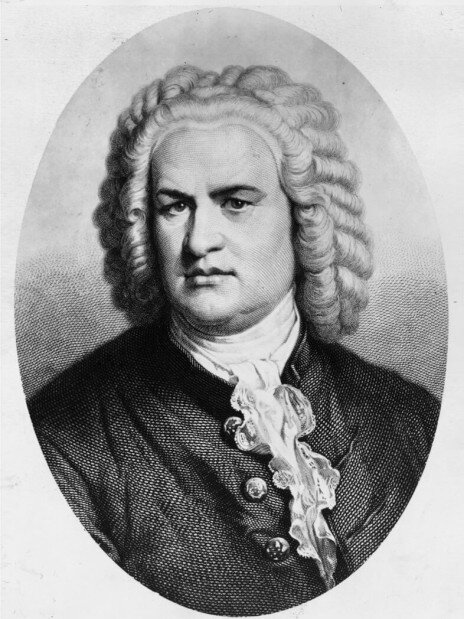

Just so you know what I’m talking about, here is the most famous recording of this most famous piece of classical music written for one of the most famous classical instruments (cello) performed by one of the most famous cellists from one of the most famous centuries of one of the most famous civilizations on one of the most famous planets on Earth:

Before I talk about this prelude, it’s important to know what a prelude is musically, because you will come across a few on my album and certainly many more in classical music. Etymologically, prelude means “fore-play” (use your imagination). Musically, it is generally a short, improvisatory piece played at the beginning of some specific collection of music. In the early days, it was improvised music performed by the church organist before the prescribed music of the service. It would have also been improvised by a court musician getting ready to play the evening’s dance music at a royal party. Because of their improvisatory nature, preludes are primarily performed by soloists. By the time Bach wrote his preludes, of which there are quite a few, it became standard to actually write them out for the musicians since they were no longer being played necessarily in functional events (parties, balls, church services) but in music-as-performance for a listening audience. After Bach, preludes became standalone compositions and a term that applied to any short and loosely structured composition that didn’t necessarily fit into any other category. There are a couple of these on my album as well, such as Heitor Villa-Lobos’ Prelude No. 4 in E minor (“Homage to the Brazilian Indian”).

So what about the Bach preludes? I’ve included two of Bach’s preludes on my album—the other being from Cello Suite No. 3. What I love about these pieces is the freedom they allow the performer. You can really learn a lot about a musician by how they play these pieces. Each performance is like a window into the musician’s soul. Other pieces are more standardized and their interpretations are more often indicative of skill, but with the preludes (as they are not exceedingly difficult), you learn about a musician’s soul. Why? Because they come with no instructions. It’s just a series of even, consistent notes with no performance indications. The worst musicians, in my opinion, are the ones who play it as written because then it sounds robotic. One must take creative liberties with a prelude. The other pieces that immediately follow Bach’s preludes are slightly more strict in rhythm and tempo. In my blog about Bach, I compare the preludes to Shakespeare’s monologues where the performer is left alone exposed on stage with the audience hanging on to every word and inflection. That is when the performer truly shines. The rest of the play/suite is business as usual.

So what about this prelude? This prelude is so great and famous and beautiful, in my opinion, because of the following: it opens with a memorable and repetitive figure and harmonic progression that sets up the rest of the piece followed by deviations and variations of that opening figure that take the listener through different key centers and chords starting with major diatonic triads that meander and weave into distant keys and proto-jazz harmonies in a way that remains consistently beautiful but everchanging and interesting. Most other types of compositions can be boiled down to leaving home, going on a journey, and coming home again. But preludes leave home once and for all with no return. They remind me of leaving a lakeside cabin by canoe, meandering down the river and ending up in the ocean. The ocean is the rest of music in the suite (the “meat and potatoes” if you will), but on your way to the ocean are wonderful and varied landscapes totally different from what’s out at sea. These fleeting images, each different from the last, are what make Bach’s preludes so beautiful and captivating and why I open my album with one.