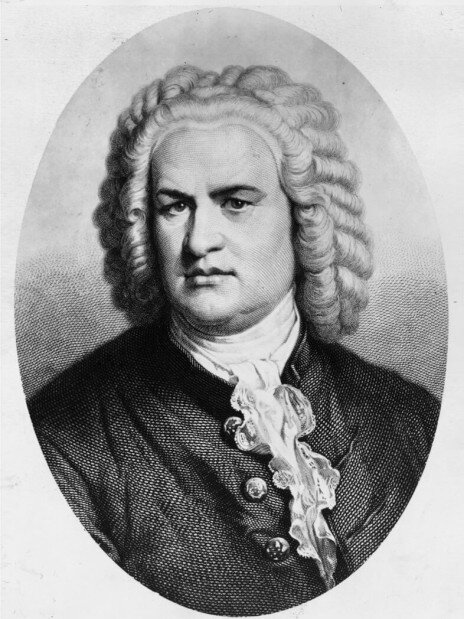

Composer Series—Johann Sebastian Bach: “The Godfather of Classical Music”

The biography and subsequent influence of Johann Sebastian Bach is too great to condense into a single blog post, too dry for non-academics, and too heavily represented by more authoritative sources for anyone that’s genuinely interested. So, I’ll keep the bio brief, the historical importance briefer and try instead to articulate why I think he’s worth our interest.

J.S. Bach lived from 1685 to 1750 and spent his entire professional life in Germany. He was destined to became the most famous (today) in a long line of family musicians when his father taught him how to play harpsichord and violin. Unfortunately, his parents died when he was nine years old and Johann went to live with his older brother who taught him to play organ. At 15, he received a scholarship for his fine singing voice and began his a career in music when he graduated at 17. He was what we would call a “church musical director” who happened to also be a virtuoso organ player, organ builder and conductor. He was a hard-working and devout Lutheran who dedicated each of his works “in the name of Jesus.”

Serious, but kind and devoted.

An organ similar to what Bach would have performed on.

Bach composed over 1,000 sacred, organ and choral works, but his other instrumental music, which he wrote mainly for personal enjoyment or for his students, is what he is best known for today. Even though Bach is now considered a genius, in his lifetime, he was just a talented, working musician. His sons, Carl Philipp Emanuel and Johann Christian Bach, both composers, eclipsed their father in fame. Bach Sr. was considered old-fashioned and largely forgotten with many of his most famous pieces today not receiving public performance until almost 100 years after his death when he was “rediscovered” by Felix Mendelssohn beginning in the 1830s. Bach’s brilliant, innovative and immensely complex use of counterpoint (multiple melodic lines weaving in and out of each other) has earned him a place at the pinnacle of the Baroque musical style.

St. Thomas Church in Leipzig, Germany, where Bach worked from 1723 to his death in 1750. Martin Luther also preached here in 1539.

I would compare Bach’s impact on the development of Western art music (aka “classical” music) to Shakespeare’s effect on the development of English literature. Each radically evolved their respective fields spawning huge advancements for hundreds of years to come. Bach’s mastery of counterpoint is still a cornerstone of classical music and required study for music students across the world. He was able to synthesize all of the different styles and techniques of his day into a more cohesive and robust musical vocabulary. Subsequent legends such as Mozart, Beethoven, and Chopin were deeply inspired by his music with Beethoven even calling him, “the original father of harmony.”

As a soloist, I am mostly drawn to Bach’s works for solo violin and cello. These works make up a tiny fraction of his overall oeuvre, but they are some of his most famous. In them, Bach condenses his cosmic genius into a bare, raw, stripped down expression of the highest divinity. In their sparseness, there is no room for error and no limit to the expressive possibilities of the individual. They are like the monologues of Shakespeare where the actor is alone on-stage almost speaking to the audience as they hang on to his every word. With no quick-witted banter going back in forth between various characters, every syllable, every articulation, every rise and fall in pitch and volume, and every breath counts.

If Bach’s larger works are kaleidoscopes aimed at heaven, then his solo pieces are microscopes aimed at the heart. The interpretation is left entirely up to the individual, not a conductor/concertmaster. Like Shakespeare, Bach also leaves NO performance or expression indications—no tempo markings, no dynamics. The only clue is perhaps the rhythm or general style of the piece. But the preludes, my favorite, do not even follow a specific style or pattern. They are just a stream of notes from beginning to end with few, if any, breaks. It is up to the performer to interpret the phrasing and expression of these notes.

I’m also drawn to Bach’s music because of it’s fractal nature. This is an entire topic for another time, but, for now, I’ll leave you with a definition and a visual example. Fractals are “infinitely complex patterns that are self-similar across different scales.” In other words, if you were to zoom in, or out, infinitely, the same shape would continuously appear. This phenomenon occurs all throughout nature: trees, blood vessels, lighting bolts, rivers, broccoli, neural networks, galaxies, etc. In my opinion, it is one of the fundamental forces governing the universe and exists at every level from the microscopic to the cosmic. I will save the fractal analysis of Bach’s music for another time, but the fact that Bach was operating at such a profound level—before the mathematical basis for fractals was even conceived—reveals his genius and the infinite opportunities for performers and listeners to understand his music.